by Gabi Clayton

with some stories by Naomi Schott and additional research by Noel Clayton

This started as a research paper written for a film class, “Hand in Hand: Feminist and Third World Film Theory and Practice” taught by Gail Tremblay and Marge Brown in Fall 1988 when I was a senior at The Evergreen State College.

We had just moved from Hattiesburg, Mississippi to Olympia, Washington.

My father died when I was 12 and I was out of touch with his side of the family until a few years after this was written, so the family history originally came mostly from my mother’s memory. Then things were added over time as I learned new things and found photos. My son Noel did some research in 2014 and found more great information that is included. This is full of quotes from other people, and there is a bibliography.

For those of you who are curious, it may tell you something about me. I decided to publish it here as my personal response to a Human Rights Campaign’s Family Holiday Action Alert, which said:

“Telling the truth about who we are — even to just one more friend or relative — can start to break down walls of silence and isolation that may have taken years to build up.”

Here goes …

The painting that hung over my parents’ couch showed peasants on a farm, working in the fields, and eating lunch under the trees. It was painted at a time when some artists were moving away from painting saints and aristocrats, discovering that common people were worthy subjects. For me, that painting is a symbol of a joining of the ideals of social change and the ideals of art. Both were encouraged in me since childhood.

My dad in knickers. |  My mother in a beret. |

My dad looking left. |  My mom with curly hair. |

My mother’s father, Louis Schmidt, was an Orthodox Jew from Lithuania. When he was twelve years old, he walked across Europe, alone, to Amsterdam, where he caught a ship to join his father in New York. When he arrived on Ellis Island, an immigration official changed his last name to Smith. Welcome to America!

They were poor, and saving money to send for his mother, so Louis went to work immediately in a factory on the Lower East Side. Later, as a young man, he was studying to become a rabbi. Something caused him to break with his father and become a militant atheist (and socialist). When he married my grandmother, he was working as a trolley car operator. Later he was a subway conductor, working long hours. My mother remembers him mostly for his love of learning; he was self-educated and read whenever he got a chance. This love came from his background as an Eastern Jew, where:

Historically, traditionally, ideally, learning has been and is regarded as the primary value, and wealth as subsidiary or complimentary. (1)

Astrid ‘Nina’ Rebekka Hagerup, my mother’s mother, was the daughter of the mayor/chief of police of a seaside resort on the Norwegian coast. She was a romantic who loved gypsy music and poetry.

On 03/08/2014 my son Noel Clayton wrote:

| I looked a little into the Hagerup side of the family today and found this HUGE database of the Hagerup family. http://genealogy.hagerup.com/ Mom had mentioned a family connection to the composer Edvard Grieg so I thought I would figure out what it was. It took some digging, but this is what I found: I can find no record of the name Astrid Nina Rebekka Hagerup before her arrival at Ellis Island, but “Astrid Kingo Rebekka Hagerup” is listed on a 1910 census. She was born in the same village and the same year (1890) so is almost certainly the same person. |

| Her father was Anton Richard Hagerup b. 1866 His father was Hans Stabo Hagerup b. 1822 His father was Ferdinand Anthon (Ole) Hagerup b. 1795 His father was Christopher Abelseth Hagerup b. 1765 His father was Niels (Honningdal) Hagerup b. 1729 (took his name from his cousin through Anna Hansdtr Hagerup) His mother was Emte Hansdatter Stockberg b. 1685 Her father was Hans Frantzen Stockberg b. 1648 His second wife was Anna Hansdtr Hagerup b. 1654 (took the name from her grandmother) Her father was Hans Rickertsen b. 1589 His mother was Anne Margrethe Hansdatter Hagerup b. circa 1565 Her brother was Hans Hansen Hagerup b. 1644 His son was Eiler (Hansen) Hagerup b. 1685 His adopted son was Eiler Eilersen (Kongelw) Hagerup b. 1718 His son was Edvard Eilersen Hagerup b. 1781 His daughter was Gesine Judithe Hagerup b. 1814 Her son was Eduard (later known as Edvard) Hagerup Grieg b. 1843, the composer |

| So: Astrid’s father’s father’s father’s father’s father’s mother’s stepmother’s father’s mother’s brother’s son’s adopted son’s daughter’s son was the composer Edvard Grieg. Making the three of you fourth cousins seven times removed by way of a second marriage and an adoption. Not exactly a close connection but it’s fun what you can find. |

When she left home, she found that the only skills she had were domestic, so she worked as a cook and ladies’ companion in England for two years before coming to New York. There, she met Louis Smith when she was almost dead from an (illegal) abortion. Louis nursed her back to health; they married and had two daughters. I’m sure my mother’s love for the arts, especially literature and music, is a gift from her mother.

Louis died in 1935 when my mother was 16 years old. Within a year, Astrid married Thomas Lappin, a Communist shipyard mechanic from Scotland. Tommy had arrived in New York during the Depression and was lucky to find a job as a janitor. He had dropped his party membership because he did not believe that Russia should dictate to other communist/socialist countries. But he remained an active Marxist, out on picket lines, organizing unions and going to meetings. Eventually he re-joined the party and sold the Daily Worker in the streets in his free time.

To my mother, Tommy gave his passion for social change, a belief that it is possible to make the world a better place for everyone.

Such poverty as we have today in our great cities degrades the poor, and infects with its degradation the whole neighborhood in which they live. And whatever can degrade a neighborhood can degrade a country and a continent and finally the whole civilized world, which is only a large neighborhood… The old notion that people can “Keep themselves to themselves” and not be touched by what is happening to their neighbors or even to people who live a hundred miles off, is a most dangerous mistake, The saying that we are members of one another is not a mere pious formula to be repeated in church without any meaning; it is a literal truth, for though the rich end of town can avoid living with the poor end, it cannot avoid dying with it when the plague comes. (2)

My father’s mother, Emma Dellheim, came from a family of middle-class Jewish shopkeepers in Mutterstadt, Germany. She married Ferdinand Schott, a wandering Jewish socialist, Emma’s brothers considered Ferdinand a “neer-do-well”, but they helped the couple open a haberdashery anyway.

Ferdinand was a funny loving, gentle man who posed for my father’s camera in the snow wearing nothing but his rolled-up long johns and a hat. My sister Mimi reminded me that he did other kooky things too. He once kept a live frog in his mouth and went to a dinner party, and when the time was right, he opened his mouth and let the frog jump out onto the dinner table – to the horror or maybe the amusement of the dinner guests!

When my father was thirteen years old, in 1933, the Nazis became the most popular party in Germany, it had become a dangerous place for Jews to live, even for those, like the Schotts who were proud of their heritage but not particularly religious. With financial help from Ferdinand’s wealthy brother Max Schott who lived in Colorado, my grandparents and father were able to escape to France.

Grandma Emma was a woman who had no sense of humor, and now I know it was at least in part because Ferdinand was a philanderer. Our second cousin Arthur told my sister that Ferdi had an affair with a woman who was not Jewish which was illegal, and the woman got pregnant. Arthur says we have a relative in Germany – Ferdinand’s daughter from the affair – who we hear wants no connection with our family. So, though I first understood that the family knew it was getting dangerous there with Hitler coming into power and left because of that, but now I know Ferdinand’s behavior was real reason they left Germany.

My father was sent to a boarding school in England, for his further safety. Emma and Ferdinand were sent to an internment camp when Hitler occupied France. When the war was over, Max helped them move to New York City. They died within days of each other in 1956, when I was three or four years old.

Being a Jew is not cause for despair or depression; such despair and agony as the Jewish people have had to endure over the past thousand years is the result, not of what they are, but of what the Christian world has inflicted upon them; and since so many Jews stubbornly remained Jewish in spite of that, the fact of being Jewish must hold an enticement in itself.

I think there will always be Jews — if only because the fact of being a Jew is a special kind of wonder… a condition of civilization, of being a little bit of an outsider with the outsider’s point of view, so that at least some of those who are Jews see the world more clearly because they are apart. The world needs its outsiders… (3)

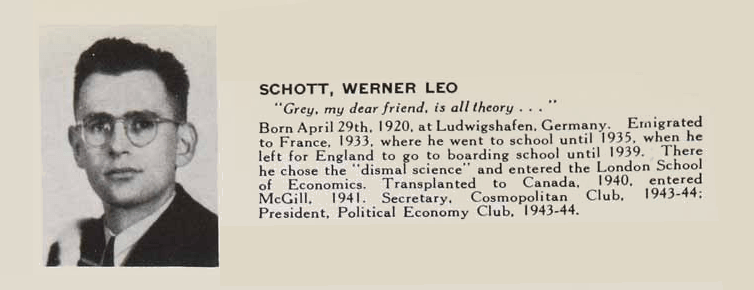

My dad, Werner Leo Schott, was born on April 29, 1921 in Ludwigshafen, Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany. He was first sent to an English school for refugee children, then to Dartington Hall, a progressive high school in the town of Totnes. When he graduated, he entered the London School of Economics.

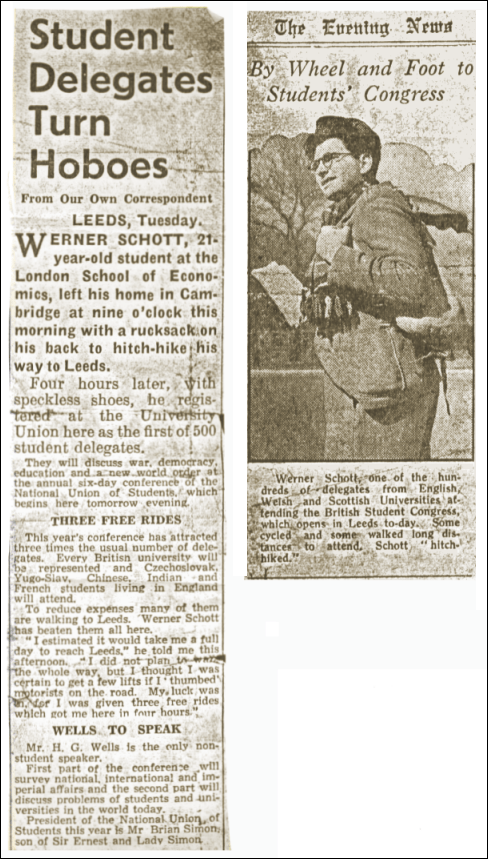

Werner Schott, 21 year-old student at the London School of Economics, left his home in Cambridge at nine o’clock this morning with a rucksack on his back to hitch-hike his way to Leeds. Four hours later, with speckless shoes, he registered at the University Union here as the first of 500 student delegates. They will discuss war, democracy, education, and a new world order at the annual six-day conference of the National Union of Students… (4)

“In June and July 1940, 2,354 Austrian, German and Italian male refugees, aged 16 to 60, are sent to Canada. Many of them will stay imprisoned in Canada for more than 3 years.” – Internment of Jewish refugees in Canada, Anne Frank Guide. (Also see The Vancouver Holocaust Education Centre.)

So, the British government decided that my father was an “enemy alien” because he was a German. He was put on a ship and sent to a Canadian internment camp. On the ship and in the camp were other German Jewish refugees, and another group of “enemy aliens” — German Nazis. Although I understand they were separated, it shocks and confuses me when I think of them being together at all, lumped into the same category.

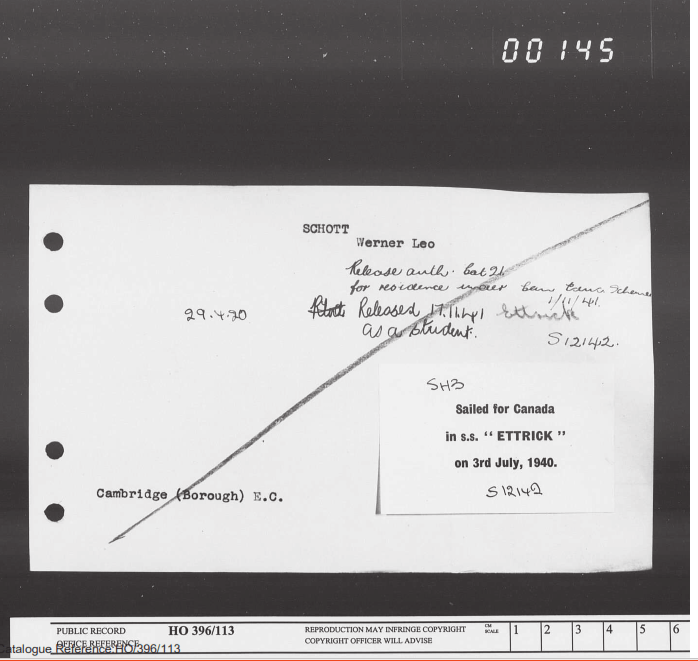

On 01/02/14 Noel wrote: “I was doing some genealogy research this morning. I managed to find this record in the British National Archives. Don’t know if you’ve ever seen it.”

On 02/01/2014 Noel wrote:

| In British Policy and the Refugees, 1933-1941 By Yvonne Kapp, Margaret Mynatt: “Further revelations were provided by the incidents of the MS Ettrick and the SS Dunera. The following description of conditions on the MS Ettrick has been compiled from reports by two of the passengers: “The M.S. Ettrick left Liverpool on 3rd July 1940 with 1,300 internees on board of whom over 1,200 were refugees. “Twelve hundred and eighty-four people were herded together in the bows of the ship in a three-tierd space with a shaft in the centre. The three tiers were connected by companion ways – the top tier was at about sea level. Most of the space available for these 1,284 people was taken up by the dining tables, benches, the shaft and the companion ways. At the top level, which was naturally a larger space than the bottom tier in the hold of the ship, over 500 people lived and slept for twelve days and nights. Another 500 prisoners were put in the Sargent’s Mess. There were a few ratings on board, but most of the guards were soldiers. There were some German prisoners of \war, kept apart from the internees and evidently in quite decent conditions; they had cabins to sleep in and seemed to be allowed on a certain part of the deck at any time of the day. In the event of an emergency the only way out for the internees on the lower tiers would have been the companion way and from there to the lower deck, but at the top of the companion way there was a barbed wire barrier which left a space of some 4ft. for passage during the day, but was entirely closed and under military guard during the night. To reach the upper deck and the lifeboats the prisoners would have had to get through another barbed wire barrier and two further companion ways which were always heavily guarded while the doors at the top of the companion ways were kept locked.” I had found the date of Werner’s deportation and other bits and pieces before, but finding this record and especially the name of the ship he sailed on gave me a whole new area to research. It led me to several historical records and personal accounts. I was going to jot down a few more interesting bits to send to you, but I kept finding more and more. Over the course of the day it kind of turned into an essay. A lot of what I found is from Google Books online previews of several out of print books, which maddeningly cut off in the middle of the story. I might have to actually find copies of the books, but this is what I pieced together. About 2,400 “enemy aliens” (mostly Germans and Italians) were detained in May and June of 1940. Most of them were told that this was a temporary measure. But then they were taken to Liverpool to board a ship to take them to internment camps in Canada along with a handful of actual German prisoners of war. The ship was the Arandora Star, but there wasn’t enough space, so about 1200 were kept in Liverpool to wait for another ship when the Arandora Star left on July 1, 1940. The next day, the Arandora Star was torpedoed by a German U-Boat and sank. Because the detainees were crowded below decks with barbed wire fences blocking the exits, over half of them died. The remaining detainees in Liverpool including Werner departed on the SS Ettrick the next day. News of the sinking of the Arandora Star spread through the ship within a few days, but the ship completed the trip without incident. There is a detailed account from those on board which I found in an excerpt from “British Policy and the Refugees, 1933-1941”. The detainees were locked below decks and only allowed to go topside in 2 hour shifts during the daytime after they got out of sight of the British coast. There were not nearly enough beds or hammocks so they slept on any flat surface available including benches, the floor and on top of each other. They suffered from seasickness and an “epidemic of diarrhoea” made worse by lack of access to the lavatory and not enough buckets to go around. When the ship arrived in Quebec on July 13, Canadian soldiers confiscated the personal belongings of some of the detainees. They were then arbitrarily assigned to one of two internment camps, either Camp “L” in Quebec City or Camp “Q”, a prison farm near Monteith, Ontario. (From “Blatant Injustice: The Story of a Jewish Refugee from Nazi Germany … By Walter Igersheimer). Several detainees filed complaints about their treatment which led to several soldiers being court martial-ed and eventually to a few heated exchanges in the House of Commons. Meanwhile, the sinking of the Arandora Star created a lot of controversy in Britain. A few days after the attack about 200 detainees who were deemed in good health were loaded onto the Dunera and set sail again. The Dunera was also attacked, but narrowly escaped. During the voyage, many of the detainees had their possessions stolen or thrown overboard by the British military guard. They arrived in Australia two months later starving and suffering from dysentery. The loss of life and poor treatment of the survivors of the attack caused an outcry which led the British government to halt further deportations and began releasing some detainees. In October of 1940, the detainment camps in Canada were reorganized, possibly as a result of the uproar over the detention program in Britain. Both Camp L and Camp Q were closed on October 15. The detainees were split up largely by religion and moved. Most of the Jewish detainees (probably including Werner) were sent to a new camp in Newington, now part of Sherbrooke, Quebec called variously Camp N or Camp 42. Although Britain was starting to release many detainees, particularly Jewish ones, the Canadian government was distinctly anti-Semitic. Frederick Charles Blair, the director of the Immigration Department, believed there was an international Jewish conspiracy to circumvent Canada’s immigration policies by sneaking into the country as refugees. Camp N had been hastily built in an old railroad repair facility and wasn’t complete when 618 detainees arrived. It wasn’t fit for human habitation. “The railway track and oiling pits that ran through the sheds were filled with black water. The place had six-old fashioned lavatories without ventilation, two urinals and seven low pressure water taps which also had to serve the kitchen. The windows were broken and the roofs were leaky; so were the noisily hissing heating pipes.” (Eric Koch as quoted in “Prisoners of the Homefront: German POWs and “Enemy Aliens” in Southern Canada” by Martin Auger). Some of those buildings are still standing and now form part of Talbot Prison and a bus rental company. As the restrictions on Jewish detainees continued to loosen, they were reclassified as refugees and conditions improved in the camps. Some were returned to England. Some chose to remain in Canada. Those who stayed had to be sponsored by a Canadian civilian or institution to be released. Many of them were able to take the matriculation exams for admittance to McGill University in Montreal. I assume that is the reason for the note on Werner’s internment card [above] that he was released as a student on November 17, 1941. [Interesting because I had always thought that my dad was interned for the whole of WWII.] |

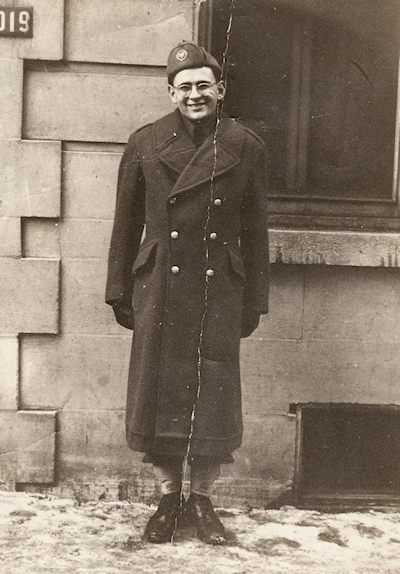

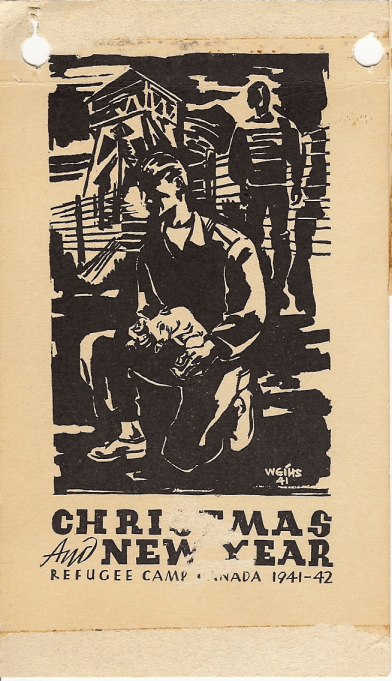

Here is a photograph of my dad – on the back it says: “In Canada Camp during second World War.” And a 1941 Christmas card from his internment camp.

|  |

| Werner Schott in Canadian camp during Second World War. | Christmas & New Year card, refugee camp 1941-42 – Werner Leo Schott. |

In the camp, my father joined a Marxist study group.

It’s really a wonder that I haven’t dropped all my ideals, because they seem so absurd and impossible to carry out. Yet I keep them, because in spite of everything I still believe that people are really good at heart. I simply can’t build up my hopes on a foundation consisting of confusion, misery and death. I see the world gradually being turned into a wilderness, I hear the ever approaching thunder, which will destroy us too, I can feel the sufferings of millions and yet, if I look up into the heavens, I think that it will all come right, that this cruelty too will end, and that peace and tranquility will return again. In the meantime, I must hold up my ideals, for perhaps the time will come when I shall be able to carry them out.(5)

Want to know more? See: “Enemy Aliens” The Internment of Jewish Refugees in Canada, 1940-43 – by Vancouver Holocaust Education Centre.

During World War II my mother, Naomi Ruth Smith, joined the army as a registered nurse and worked very briefly in a military hospital in North Carolina, but after a very short time she was diagnosed with tuberculosis and was given a medical retirement with a pension which she received to this day. (Note: mom was still alive when I wrote this. She got the pension until she died.) She credits having that income as a major factor in her independence and being a feminist, but she would sometimes worry that if she was too politically radical the government would find a way to discontinue it.

My mother spent time in a tuberculosis sanatorium in North Carolina one mile from Black Mountain College. She told me she walked through the woods to the progressive college to take violin lessons, attend occasional lectures, and for parties. She was impressed with the atmosphere of openness. Among the faculty and students were “people of every shade of political opinion, from Marxist to Nazi to Capitalist.” (Here is a new article about Black Mountain College that I think is great: Art as a Learning Process: The Legacy of Black Mountain College – I can see why my mother was impressed.)

I am not clear on what she studied where after that. I think she received a bachelors degree in Pre-Social Casework at New York University (NYU) and then got her masters degree in Social Work from the Smith College School for Social Work which I know she was an alumnus of.

When he got out of the internment camp my father went to McGill University and graduated with a degree in Economics and Political Science. John Grierson, the documentary filmmaker was looking for an apprentice film editor with a background in Political Science. My father was hired and worked with Grierson at the Canadian Film Board, where he made friends with Norman McLaren and others.

| The Ottawa Journal › 1944 › May › 20 May 1944 › Page 19 – found by Noel. Ottawa Girl Wins Award at McGill ” MONTREAL. May 20. CP) . Joan -Deborah Levinson, of West– mount. Que., won the Governor General’s Gold Medal for modern languages and literature; it was . announced in the list of graduates of McGill University issued today. The total list of degree and diploma winner totalled 411 names, and they will receive their awards at the General Convocation, May 23. Other prize winners included: Werner Leo Schott, New York, Allan Oliver gold medal and Allan Oliver fellowship, with first class honors in economics and political science. Ernest Wirid Legrls, Halleybury. Ont, University scholarship, British Association medal and Montreal Light, Heat and Power Consolidated second prize, with honors in electrical engineering. Beatrice Ellen Louise Law, Calgary, Alta, food conservation prize, with second class honors in home economics. Janet Ritchie, Ottawa, Montreal Local Council of Women’s prize in nutrition, with first class honors in home economics And about the award: Allen Oliver Fellowships Established by Mrs. Frank Oliver, of Edmonton, Alta., in “proud and loving memory of her son, the late Allen Oliver, M.C., B.A., Lieutenant, 26th Battery, C.F.A., who was killed in action at the Somme on November 18, 1916.” Lieutenant Oliver was an honour graduate in 1915 in the Department of Economics and Political Science. Awarded to the students who stand highest in first class honours in each of the Departments of Economics and Political Science at the final B.A. examination. The holders are required to pursue studies in Economics and Political Science at McGill or elsewhere. No application is required. Value: $3,000 each. Werner Schott’s McGill Yearbook – found by Noel. http://yearbooks.mcgill.ca/viewbook.php?&campus=downtown&book_id=1944#page/21/mode/1up Noel wrote: “He is listed alphabetically under Arts Students (page 22), with the Cosmopolitan Club (page 199), and with the political economy club (page 222). He might be on other pages without a caption but I haven’t found him. He may also be in the group shots of the class of 1944 which are in the 1942 and 1943 editions on the same web site.” |

|

| Notes: “dismal science” refers to Economics, and “Grey, my dear friend, is all theory[, and green the golden tree of life]” is from Mephistopheles in Goethe’s Faust: A Dramatic Poem. |

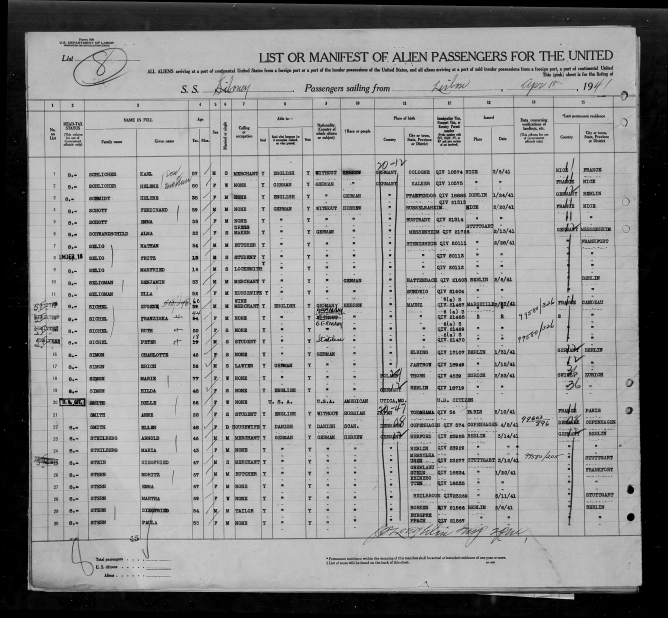

Here is the manifest for the ship on which Ferdinand and Emma Schott arrived in New York in 1941. They are on lines 4 and 5.

Noel wrote:

“I think I also found a lot of stuff on Ferdinand’s brother Max Schott. Assuming he was the Max Schott who was head of the American Metals Corporation and the Climax Molybdenum mine in Colorado, there’s a fair amount of information about him and his family. His daughter Katy was married to the artist Channing Peake and his grandson (also named Max Schott) is the author of several books and taught literature at UC Santa Barbara.”

[Note: That was our relative Max Schott. I met Max’s wife Alice Schott in Santa Barbara once – or their daughter, both named Alice. My mom found her and contacted her, and I spent a night at her house on New Year’s Eve in around 1968 while my mom took my sister Mimi and my brother Michael to Disneyland.]

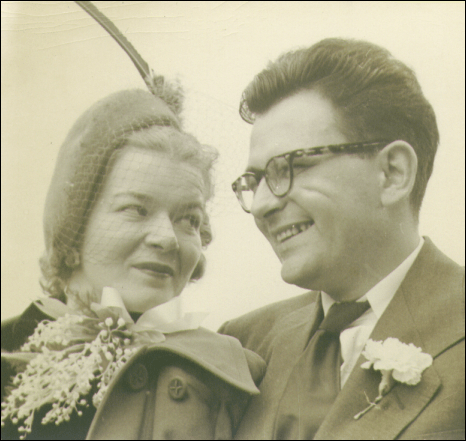

My mother met and married my father who had moved to New York for a job as a film editor and to re-join his parents.

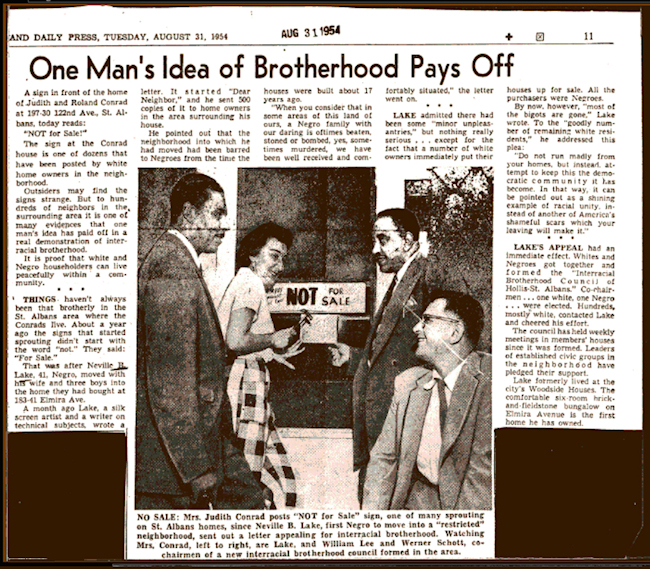

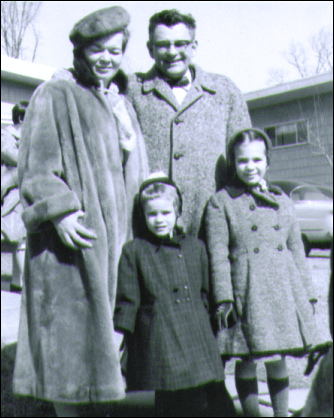

I was born in 1952. The Queens, NY neighborhood we lived in had been one of all-white, “old-line reactionaries.” Black families were buying homes there, and left-wing white families (like my parents) who believed in integration moved in also. They started the St. Albans Interracial Fellowship Council, and a community peace group that was anti-nuclear and against things like U.S. involvement in Korea and Vietnam.

Photo caption: NO SALE: Mrs. Judith Conrad posts “NOT for Sale” sign, one of many sprouting on St. Albans homes, since Nevil B. Lake, first Negro to move into a “restricted” neighborhood, sent out a letter appealing for interracial brotherhood. Watching Mrs. Conrad, left to right, are Lake and William Lee and Werner Schott, co-chairmen of a new interracial brotherhood council formed in the area.

My father turned our basement into an informal screening room for a neighborhood film society. I remember seeing children’s films there, like “The Red Balloon”, and other films too: Norman McLaren’s “The Story of Transportation”, newsreels, and documentaries. (When we recently watched “Salt of the Earth” I thought I must have seen it as a child. I called my mother and she remembered that Daddy showed it to the film society when I was a little girl.

It was a frightening time to be Marxist/Communist/ politically active/outsider/etc., but both of my parents stayed committed and involved. My mother walked on a picket line, pushing me in a stroller, to protest against the death sentence given to Ethel and Julius Rosenberg. I must have been under a year old because their execution took place in 1953. My father was working as a film editor on various projects — documentaries, newsreels, and commercials. At one point, the FBI approached a company he was working for and tried to get him fired because of his politics. An English airline pilot friend of my fathers was questioned by the FBI at the airport after staying with us between flights. They wanted to know who he had seen at our house. The government also threatened to deport my mother’s parents for their political beliefs. It frightened them so much that they moved to Florida and completely dropped out of their involvement with the Communist Party; they were afraid to even subscribe to the left-wing periodicals they had read for years.

…the old left, the left of the Communist Party in the thirties and forties, had always practiced a certain defensive secrecy. Most parties members simply did not talk openly about their political affiliations; and the investigations of the Cold War era, only one episode in a long history of persecutions, seemed to validate their habit of silence…

Today, some former party members…regret the old lack of openness… They believe that the atmosphere of secrecy made the Party seem more devious and threatening than it was, turning into exposures information that should have been common knowledge, feeding the paranoia that sustained the witch-hunts. (6)

When I read this in our readings for “Salt of the Earth”, I remembered something else I had read. It was something from Glimpses of World History by Jawaharlal Nehru. The book was from India and out of print, but my father wanted me to have it. He hunted in used bookstores for a long time and finally found it. It is his very cherished gift to me — the letters from Nehru to his young daughter, Indira. When I read the words, I feel my father speaking through them.

How shall we bear ourselves in this great movement? What part shall we play in it? I cannot say what part will fall our lot; but whatever it may be, let us remember that we can do nothing which may bring discredit to our cause or dishonor to our people. If we are to be India’s soldiers we have India’s honour in our keeping, and that honour is a sacred trust. Often we may be in doubt as to what to do. It is no easy matter to decide what is right and what is not. One little test I shall ask you to apply whenever you are in doubt. It may help you. Never do anything in secret or anything that you would wish to hide. For the desire to hide anything means that you are afraid, and fear is a bad thing and unworthy of you. Be brave, and all the rest follows. If you are brave you will not fear and will not do anything of which you are ashamed.(7)

I remember my father as a warm, loving man who believed in me completely. My memories of him include sitting with him, listening to short-wave radio from all over the world, and discussing the programs and the different languages; going to the workshop in our basement to build wooden sailboats out of scraps while he worked on some project; and going with him to his job — fascinated by the editing machines and other film equipment.

When I was a child my family belonged to the leftwing family camp, Camp Midvale in Ringwood, New Jersey. (See more about Camp Midvale by scrolling about halfway down on this page on The Tamiment Library & Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives page on Summer Camps hosted at the NYU Libraries.) We had a cabin there and went every summer until my parents divorced when I was nine years old.

Notable people who are remembered now as having visited Camp Midvale during the time our family went and later include: Herschel Bernardi, Theodore Bikel, Cesar Chavez, Jesus Colon, Ossie Davis, Ruby Dee, Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, Lou Guss, Abbey Lincoln (Anna Marie Wooldridge), George Lorrie (aka Levine), Hugh Mulzac, John Randolph, Johnny Richardson, Eslanda Goode Robeson, Paul Robeson, Robert and Michael Meeropol (children of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg), Howard Da Silva, Pete Seeger, Sonny Terry, Howard Zinn, possibly Richie Havens – not performing, just hanging out, and Sean Lennon when he was a kid. There were rumors that Angela Davis was in hiding at Midvale once, but that may not true be though the FBI came looking for her there.

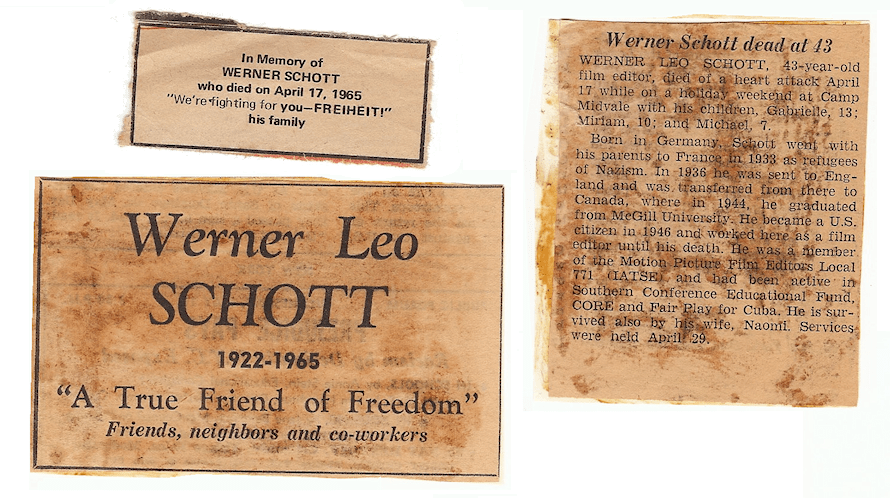

My dad died at Camp Midvale of a heart attack when he was 43 years old, and I was 12. My sister, brother and I were there with him because he had found out where my mother had illegally ‘kidnapped’ us from him — he was supposed to have joint custody but she secretly moved with us to Puerto Rico. Dad had already had heart attacks and he got his doctor to write my mother and tell her she should send us to see him because he might not live long. My mother agreed to a visit and sent us to New York City. Dad didn’t want us to go back to mom, so he put us in a boarding school (the Green Chimneys school) to hide us from her. I didn’t understand that was what was happening. He told us we were going to live with him as soon as he could get a bigger apartment and I was fine with living with him because I adored my dad. Then he picked us up at school and brought us to Camp Midvale for an Easter weekend holiday. He died that night when he had a heart attack while we were with him in the dining hall of the camp. It was a place he loved – we all did.

There is some history of Midvale here: “Escape 10: Ringwood, N.J. A Hideaway for Nature’s Friends.”

I was sad to learn that in October 1966 a suspicious fire burned the Nature Friends’ old clubhouse to the ground. The clubhouse was the dining hall/rec hall and more.

| There is lots of great historical information in: “New York´s Nature Friends: Their History, their Camps” by Klaus-Dieter Gross (Regensburg) Publiziert am 23. April 2014 von Peter Pölloth, NaturFreundeGeschichte NatureFriendsHistory 2.1 (2014). (pdf file) Peter Pölloth: “The New York local, founded in 1910, was the oldest Nature Friends branch in the USA. By the 1940s the branch ran four Nature Friends Camps. Both the locals and the camps, with the exception of Camp Midvale, disappeared due to political pressure in the 1950s. Klaus-Dieter Gross gives a historical survey of the local and its camps.” Klaus-Dieter Gross: “The closing of its Weis Center, a nature education location near Ringwood, N.J., by the New Jersey Audubon Society in 2013 had quite an unexpected effect. In an attempt at preserving the grounds and its remaining buildings, people who had grown up in the area came together to unearth the history of the property, revive memories, and collect documents of what up to the 1950s had been the largest Nature Friends camp across the USA. To these activists the following text is dedicated.” Also read this excellent piece: “Why Camp Midvale Still Matters to Me!” by Karin Adamietz Ahmed (Oakhurst, N.J.) Publiziert am 23. April 2014 von Peter Pölloth, NaturFreundeGeschichte NatureFriendsHistory 2.1 (2014). (pdf file) Peter Pölloth: “From a very personal perspective Karin Adamietz Ahmed describes a newly emerging interest in what used to be Camp Midvale, until the 1950s the biggest Camp of the Nature Friends of America. Recent events have triggered what can be seen as a resurgence of the Nature Friends idea in Northern New Jersey.” |

(Camp Midvale became The New Weis Center for Education, Arts and Recreation in 2015. I’m so glad to know it will continue. Here is an article about the process of saving the camp: An informal group of citizens calling themselves “Nature Friends for Preserving Weis” has launched a campaign to prevent the facilities at Weis Ecology Center on Snake Den Road from being torn down. )

My father had tickets to take us to the Freedomways magazine’s celebration tribute of Paul Robeson’s 67th birthday in New York City on April 22nd. After my dad died of a heart attack on April 17th my mom found the tickets and she took us because she knew dad wanted us to be there. The Freedomways celebration was produced by Harry Belafonte and chaired by Ossie Davis and Ruby Dee at Hotel Americana in New York City. It was attended by 2,500 people and it was Robeson’s last major musical performance. Among the 60 sponsors and those paying tribute to him were James Baldwin, John Lewis, Earl Dickerson, Dizzy Gillespie, John Coltrane, Linus Pauling, Earl Robinson, Pete Seeger, Billy Taylor, Olatunji, and I.F. Stone. I wish I remembered more of that night. The event’s program is archived here in Temple University’s archives.

“When Paul Robeson returned home from overseas in the early 1960’s from a triumphant tour of concerts and theatrical performances, Freedomways Magazine a great ‘Welcome Home” salute in his honor a the Hotel Americana in New York City on 22 April, 1965.”

“HE SANG FOR US ALL” Statement by Mrs. Esther Jackson, Managing Editor of Freedomways in, DIMENSIONS OF STRUGGLE AGAINST APARTHEID A TRIBUTE TO PAUL ROBESON.

and

“Mr. Robeson’s last New York appearance was in 1965, when he sang “freedom” songs as guest of honor at an Americana Hotel benefit for Freedomways, the black quarterly magazine.”

Robeson, at 75, Is Feted in Absentia – by Laurie Johnston, New York Times, April 16, 1973

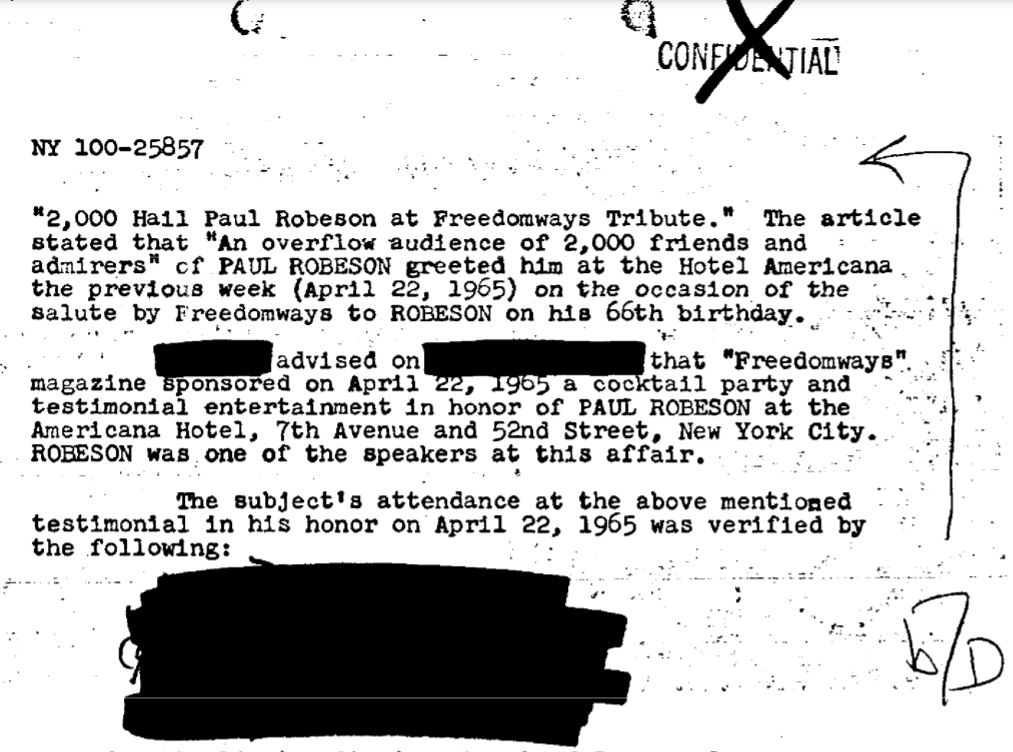

“2,000 Hail Paul Robeson at Freedomways Tribute.” The article stated that “An overflow audience of 2,000 friends and admirers” of PAUL ROBESON greeted him at the Hotel Americana the previous week (April 22, 1965) on the occasion of the salute by Freedomways to ROBESON on his 66th birthday.”

On page 79 of an FBI report on Eslanda Goode Robeson (Paul Robeson’s wife) – NY 100-25857 (PDF file)

[redacted] advised on [redacted] that “Freedomways” magazine sponsored on April 22, 1965 a cocktail party and testimonial entertainment in honor of PAUL ROBESON at the Americana Hotel, 7th Avenue and 52nd Street, New York City. ROBESON was one of the speakers at the affair.

“The subject’s attendance at the above mentioned testimonial in his honor on April 22, 1965 was verified by the following: [redacted] “

I see that without always being aware of it I have believed and tried to connect with what I was taught through words and examples as a child. The important things are love, art, and a commitment to social change, I became a practical nurse. I worked for years for room and board for a social service organization in New York City, and with my husband in Mississippi edited first a weekly newspaper and then a magazine devoted to the arts. We also ran a shelter for homeless persons, including battered wives. At the age of thirty-three, I went back to college, and after two years as an art student changed my major to film and video production. As a student I discovered, or rediscovered, a number of artists whose statements have touched something in me, who have, as the Quakers say, spoken to my condition. One artist/ poet who has had a particular impact on me is Kenneth Patchen, who said:

Why shouldn’t you think it’s crazy to believe in a green deer? All your life you have been taught to believe in only what you can use — to set on the table, to put in the bank, to build a house with. What possible use would a green deer be to anyone? Who would believe in a man with a blazing bush in his cart? Then let me tell you that it is beliefs such as these that are the only hope of the world. Let me tell you that until men are willing to believe in the green deer and the strange carter, we shall not lift our noses above the bloody mess we have made of our living.(8)

This class has been exactly what I have been looking for, a chance to blend form and content. Something challenging that offers me new perspectives: an education. Early in the quarter I started to realize that I was being exposed to stuff that was meant to make me think (finally!). I think the films that have made the biggest impact on me were “Thriller,” “One Way or Another,” “Made in China,” “Quilombo,” “Naked Spaces: Living is Round,” and “Salt of the Earth.” Seeing “Salt of the Earth” again, while I was writing this paper, was like being encircled by my own heritage. Although my father didn’t work on the film, I knew that it had come from people within the same Marxist tradition as my parents.

I look for ways to make meaning, not only in my own life, but shared with others, reaching across the void that separates us. I turn back to Nehru’s book and read:

Our age is a different one; it is an age of disillusion, of doubt and uncertainty and questioning… Sometimes the injustice, the unhappiness, the brutality of the world oppress us and darken our minds and we see no way out…

And yet if we take such a dismal view we have not learnt aright the lesson of life or of history. For history teaches us of growth and progress and of the possibility of an infinite advance for man. And life is rich and varied, and though it has many swamps and marshes and muddy places, it also has the great sea, and the mountains, and snow and glaciers, and wonderful starlit nights (especially in gaol!), and the love of family and friends, and the comradeship of workers in a common cause, and music, and books and the empire of ideas…

It is easy to admire the beauties of the universe and to live in a world of thought and imagination. But to try to escape in this way from the unhappiness of others, caring little for what happens to them, is no sign of courage or fellow-feeling. Thought, in order to justify itself, must lead to action…

People avoid action. Often because they are afraid of the consequences, for action means risk and danger. Danger seems terrible from a distance; it is not so bad if you have a close look at it…

All of us have our choice of living in the valleys below, with their unhealthy mists and fogs, but giving a measure of bodily security, or of climbing the high mountains, with risk and danger for companions, to breathe the pure air above, and take joy in the distant views, and welcome the rising sun. (9)

| Footnote/Bibliography: | |

| (1) Mark Zbrowski and Elizabeth Herzog, Life Is With People: The Culture of the Shtetl, 1967 (Schocken Books, NY, p I74) | |

| (2) George Shaw, The Intelligent Woman’s Guide to Socialism and Capitalism, 1928 (Brentano’s Publisher, N.Y., pp. 42-43) | |

| (3) Howard Fast, The Jews: The Story of a People, 1968 (Dell Publishing Co., p 371) | |

| (4) from The Evening News; Leeds, England. (date and author unknown) | |

| (5) Anne Frank, The Dairy of a Young Girl, 1967 (Pocket Books edition, Simon and Schuster, Inc., p, 237) | |

| (6) Michael Wilson and Deborah Silverton Rosenfelt, “Salt of the Earth” (reading for Hand in Hand: Feminist Film, theory and Practice, a class at The Evergreen State College, Summer 1988, p. 99) | |

| (7) Jawaharlal Nehru, Glimpses of World History: Being further letters to his daughter, written in prison, and containing a rambling account of history for young people, 1934 [letters written to his young daughter Indira] | |

| (8) Kenneth Patchen, from Kenneth Patchen, by Larry R. Smith, 1978. (Twayne Publishers.) first published in The Journal of Albion Moonlight, by Kenneth Patchen, 1941. | |

| (9) Nehru, p. 989. |

Sharing this is probably a bigger deal for me than you may realize. Being open and honest with people about my family history or cultural background (or whatever you want to call it) is a scary process for me. I think I lived in Mississippi way, way too long – eleven years.

I remember one of the first days there – I was pregnant with Bill, and Noel was a little guy. It was 1977. We went to downtown Hattiesburg with Alec’s parents, to the store they owned (sporting goods, house paint and stamps & coins). They always parked at the gas station across the street from the store. We got out of the car and Alec’s mom introduced me to the man who ran the station. I can’t remember now if she told him that I was from New York or if he reacted to my accent, but he turned to Alec and said, “Whadj’a do – marry you one of them New York Jewish princesses?” Alec remembers it different – that the man said “Yankee bride”, and that someone else called me “a New York Jewish princess” later. But whatever the man said, it wasn’t a friendly, joking comment. I think it was the first of many times that I realized how very much of an outsider I was there. Although we made some good friends, I almost never shared my background with people. It didn’t feel safe.

And yet, we went on to publish an alternative newspaper that spoke out against all kinds of injustice for many years. We did crisis counseling and ran an emergency shelter from our home, and wound up sheltering many, many battered women and their children – causing one minister to tell his congregation that we were “Commies” who were taking men’s property away from them. I can’t tell you how many nights I went to bed wondering if I would wake up to a cross burning in our yard.

Finally we “burned out” – we were doing too much and had little support from the community. We were exhausted, so we closed the shelter, changed the newspaper into a statewide arts and literary quarterly magazine (which was named one of the 100 Best Fiction Markets in America by Writer’s Digest magazine), and finally went bankrupt.

In some ways, that experience (the whole time in the deep south) has been the closest I have come to a personal understanding of what it feels like to live in the closet, and how very hard that can be on the soul.